How to Cheat at Structuring Your (Popular Fiction) Novel

There's no need to reinvent the wheel; use reverse outlining instead!

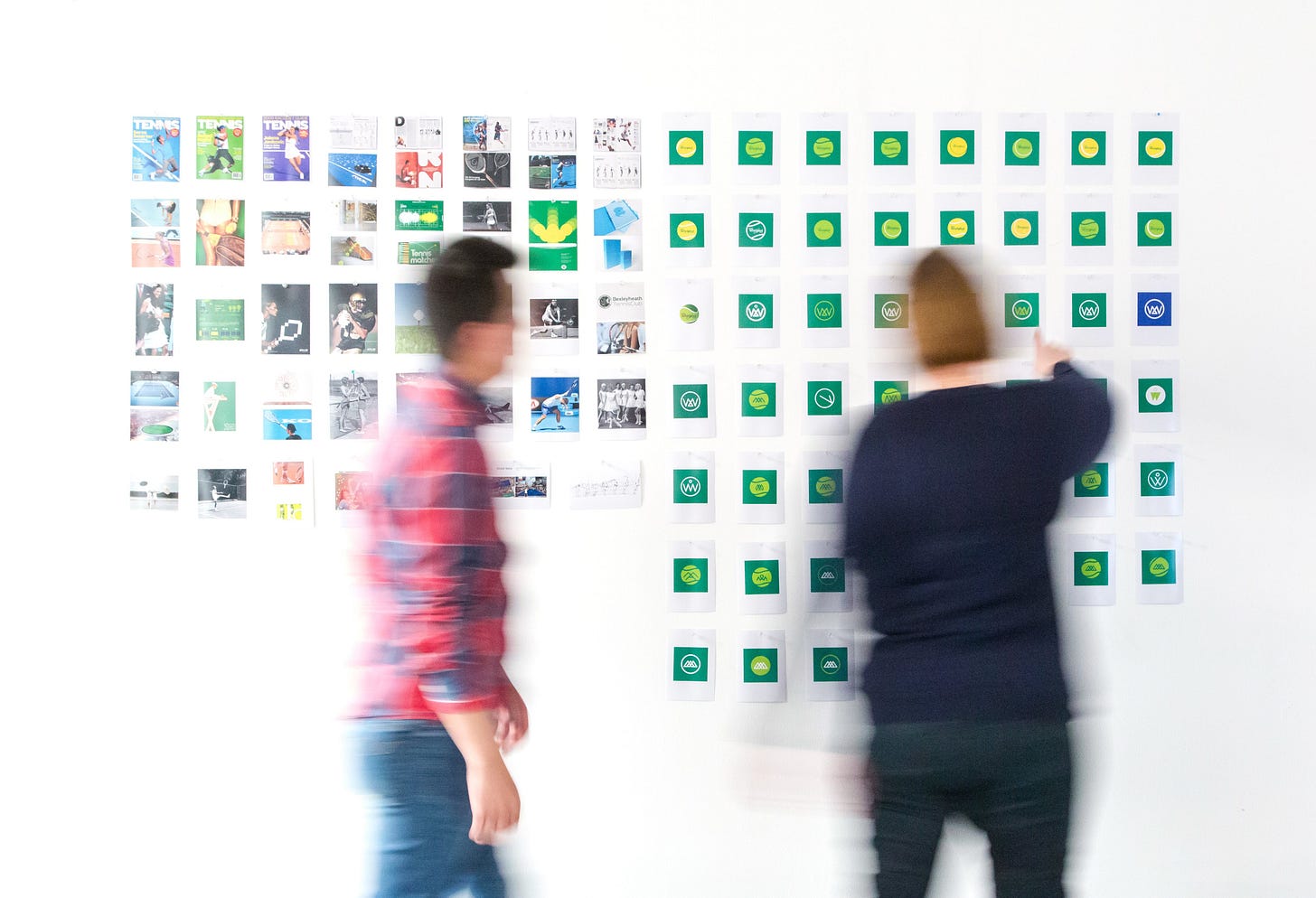

Photo by Brands&People on Unsplash

Published authors often gripe about the number of people who approach us with a “great idea,” and “all” we have to do is write it for them for a portion of the profits! Why we gripe is because, as anyone who has actually written a book knows, ideas are like unsightly chin hairs. They are constantly, reliably sprouting, no matter how many we pluck, and usually at the most inopportune moment.

Ideas are easy—writing is hard.

Part of the reason writing is hard is because most people can “see” a great idea in terms of a few scenes. They can envision the inciting incident (discovering the body, meeting the love interest, gaining a magical power). They can envision the ending (justice, a wedding, a conquering hero). And they might even envision a few “meat” scenes in that sandwich: a fight scene, a first kiss, meeting a mentor.

But how does somebody fill in the rest?

There are tons of googleable resources helping to supply such filling. There are loads of “beat sheets,” or three act structures to fill in. There’s Save the Cat and there’s the Snowflake Method. All of these are great! And if you’ve used them and they’re working for you, wonderful.

I have also found these resources helpful, and they’re great for introducing the concept of things like beats, acts, and structure to students. But when I’ve tried to use them in my own writing, I’ve usually found them confusing. Partially because they’re so rigid and partially because they’re often written to be cross-genre. So they talk about things like “dark night of the soul,” or “mid-point,” or “pivot,” or “crisis.” Sometimes these terms are helpful, sometimes not so much. Often I’m left wondering, “but what does a pivot look like in THIS sub-genre??” A “pivot” in a thriller will look much different than that of a cozy mystery, let alone in an epic fantasy.

I also didn’t use these resources when I wrote my first book, which I wrote having no idea what I was doing but having a great background in literary criticism (I’d just finished my Ph.D.). The method worked, and my first novel was published.

What I did back then was I sat down with a few of the books I admired and that were mostly closely what I wanted to emulate. And, this is important—when I say “emulate” I do not mean “copy.” I didn’t want to recreate their plots. What I wanted to recreate was HOW THEY MADE ME FEEL. In other words, there were elements of them that resonated with me: I liked how they were about unlikely heroines, and that they were kind of a slow burn, and that they were a little chilling and had good pacing, even as they gave me the sort of character evolution I loved.

Another reader might resonate with super faced paced book that really keeps them on the edge of their seat. Or they might resonate with a book that really engages with social justice issues, but through the lens of magic or science. Or they might resonate with recent historical romances that figure out how to give women of their period agency despite the constraints of their time.

So once I had a few examples of the books that gave me the right feeling, in terms of tone and pacing and engagement with themes, I sat down and reverse outlined them.

Reverse outlining is an academic technique we use to revise essays. In fact, you may have checked out the OWL Purdue’s great site on Reverse Outlining in a composition course, or a similar resource elsewhere on the interwebs.

The technique asks that you sit down with your paper, and for every paragraph, you write a VERY short synopsis of what that paragraph argues. Once completed, you have an outline of what you actually wrote, rather than an outline of what you intended to write. From that, you can figure out if your structure works, and what you can move around, add, or delete if it doesn’t.

This is also a great technique for revising whole novels if, instead of synopsizing each paragraph, you synopsize each scene and use that document to “see” your novel holistically. If you’re interested in this as a revision technique, there are resources on the internet—just search “reverse outline a novel.” I now use this technique for every book I write.

But when I first used this technique, I used it to figure out how the authors I admired made their books. I used it, basically, the same way a mechanic might take apart an engine to see how it works.

What’s crucial is not to be interested in the details of the scene. It doesn’t matter that this is the scene where Sookie is wearing a yellow dress and Bill is clearly attracted to her and she’s confused about her feelings and then she goes home and takes a bath.

What does matter is how this scene pushes the plot forward. For that, ultimately, is the goal of every scene in your book. Some scenes push the plot forward an inch, some a few feet, some a mile. But they all push the plot forward.

So my reverse outline of a book might look like this:

Introduce main character and how she’s stuck. Hint at Big Problem.

Introduce that she’s Not Normal. Inciting incident.

Aftermath in “normal” life scene

Aftermath, secrets revealed/magic revealed scene (CHASE SCENE)

Explanation of above/promise of next action (EXPOSITION SCENE)

etc.

The book I’m reverse outlining here is my first novel, and what’s important is all the detail I left out in favor of what moves the plot forward.

So, for example, in the first scene I didn’t write about the details of the main character, Jane, or what her big problem is. That’s not important, as you’ll have your own main character, and your own Big Problem. What is important is that you know you need to introduce not only your main character (duh!) but what’s at stake, immediately. Knowing there is something at stake, even if we’re not entirely sure what it is, moves the plot forward. Knowing Jane has black hair and works at a bookstore, does not. Likewise, we don’t need to know that the inciting incident is her finding a body. What’s important is that this inciting incident happens super early on—a very early way of shoving the plot forward.1

Similarly, in chapter 4, we have a scene with a lot of exposition (an “explanation” scene) but it still moves the plot forward, by promising more action (I promise to deliver an investigator who will want to work with my main character).

What I can also see from this outline, and why it’s important to keep explanations as short as possible, is the rise and fall of action. I have a (not as exciting) exposition scene following an action scene, in this case a chase scene. I can see the pacing of this novel, and I will even demarcate it by putting either in the description or in parenthesis things that are action scenes: fight scene, sex scene, battle scene, first kiss, magical duel, hiding scene, etc. I can do that with my non-action scenes, as well: exposition scene, discussion of aftermath scene, fallout scene, evaluation of suspects scene.

What you won’t see in your reverse outline of most published novels is:

Fight scene

Fight scene

Fight scene

Exposition scene

Exposition scene

Exposition scene

You normally see these scenes interspersed amongst each other, so you know to intersperse your own more action/less action scenes.

What’s great about this method, meanwhile, and what makes it different than the more generalized structural maps you often find on the internet, is that you’re getting an example of your specific subgenre. So, in my above examples, cozy and traditional mysteries LOVE an “evaluation of suspects” scene, often have two or three, and in every example I can think of there is at least one. But thrillers often do not have these kinds of scenes at all. These are all shelved under “mystery” and yet they have very different reader expectations.

Finally, that idea of reader expectation is another reason that it’s super helpful to research, through reverse outlining, what recent, published authors are giving readers. It helps you figure out reader expectation—especially if you’re using writers who gave you what you wanted, even if you didn’t know you wanted it. Times change, reader expectations change, and a lot of those beat sheets stay the same. Or, what you might fill in for “Crisis Moment” is what you’re used to reading, including what you were used to reading ten years ago… that no one wants to see anymore.

A really obvious example of this is how a lot of romance novels now end with an HFN (or happy for now) rather than an HEA (or happily every after). Another example is how rape tropes were super common in a lot of genres, as what moved the plot forward, and now are largely avoided and looked askance at.

So, for best practice, use recent novels that you loved. The kind of novels you don’t think “how did she write this, I could never,” but the kind of novel you think, “This. This is what I want to write.”

Reverse outline it! Look under the hood. Figure out how the sausage is made. Insert whatever metaphor works for you—just be sure you’re concentrating on how that writer moves their plot forward using their specific subgenre’s reader expectations.

They hooked you, after all! Figure out how they did it, and you can hook your own readers.

Thanks for reading! If you like this and ended up here randomly, feel free to:

Or share!

And if you feel like buying me a cheese stick, go right ahead! Click support for an order, membership for monthly cheese sticks! xoxo

At the same time, if I were reverse outlining Tempest Rising, I’d clock that finding a body is an option, and I’d note that clearly this book is going to have a mystery subplot, and I’d keep an eye on how this author did so, thinking through whether I would want to do something similar and how I might do that. When I did this exercise in reality, a few of the books I outlined had mystery plots (these turned out to be urban fantasy) and one or two were actually paranormal romance, so doing this exercise also helped me think through which I preferred. UF won, but that was a personal choice.